I love teaching for a lot of reasons. One of the reasons is because I learn so much when I teach. Sounds weird doesn't it? Why would the person teaching be learning? Well, It's probably not what you think. Some of what I learn comes directly from the students, but a lot comes from debugging issues on the fly and some dumb-luck discovery when someone in the class accidentally clicks somewhere or mistypes something. Recently I was teaching a class, and a combination of these led to a pretty neat discovery that I want to share with the community.

What is Mass Assignment?

There's this thing called Mass Assignment. It has other names, which I'll mention later, but for the purposes of this article, we'll call it Mass Assignment. It was originally discovered as an issue with Ruby on Rails active record. It exists where request parameters are bound directly to model objects that are ultimately used to create or update a record in a database. To understand what that actually means, let me back up a bit and explain a few things. In the Model View Controller (MVC) development architectural pattern (most common today), developers often use these things called Object Relational Mappers (ORM). Basically, an ORM abstracts (adds a layer of code) to database interaction so that instead of writing raw SQL queries that Create, Read, Update or Delete (CRUD) data in a table in a database, the developer interacts with objects that are instances of a model. This has many benefits. One being that instead of dynamically mixing user input with pre-built SQL queries, which often leads to SQL injection, user input is passed to the ORM, which safely handles it and prevents injection attacks. In order to make it easier to understand what exactly a model is, think of it as the table schema for a table in a database. It describes the columns (attributes) that make up the rows (objects) in a table (model).

For example, let's say our table (model) applies this schema:

+-----------------+

| users |

+-----------------+

| username | TEXT |

| password | TEXT |

| role | TEXT |

+-----------------+

Using an ORM, instead of making a raw query to insert a record into the table like:

INSERT INTO users (username, password, role) VALUES ('lanmaster53', 'correcthorsebatterystaple', 'user');

The developer can create a new instance of the model (row) and assign values to its attributes (columns) like:

user = User()

user = user.username='lanmaster53'

user = user.password='correcthorsebatterystaple'

user = user.role='user'

db.add(user)

db.commit()

or:

user = User(username='lanmaster53', password='correcthorsebatterystaple', role='user')

db.add(user)

db.commit()

And a new row is made in the table with the provided attribute values in the corresponding column. All of these examples effectively do the same thing. Hopefully this makes sense, because this is where the issue exists. Let's move forward.

The attributes in the above code blocks (username, password and role) could also be parameters in a request. Consider the following POST payload:

username=lanmaster53&password=correcthorsebatterystaple&role=user

In modern frameworks, a developer would access these values on the server from the request using something like request.form, which is an array of the name-value pairs. What's also possible in modern frameworks, is the ability to pass an array to a function as is, while signaling to the system that the array should be expanded into name-value pairs and treated as parameters. For example, take the following block of code:

def example(x, y, z):

#do something with x, y, and z

array = {

'x': 1,

'y': 2,

'z': 3

}

This function could be invoked like:

example(x=array[x], y=array[y], z=array[z])

But it would be a heck of a lot easier to do something like:

example(**array)

Which is shorthand for the previous example. Such a nice feature, right!? It exists pretty much everywhere.

Now look back at our POST payload example above. Some of you may have already picked up on this, but what kind of application allows the user to control what role they get? Not a good one, right? Obviously it depends on the context, but this isn't something that should normally be done. So the POST payload would probably look more like:

username=lanmaster53&password=correcthorsebatterystaple

Notice the lack of role parameter. The developer is likely setting the role attribute to user on the server because that should be the default state of every new user. That's a good thing. As we already established, the role shouldn't be controlled by the user. But this is where it all comes together. What if the application is using the really nice feature from above (we'll call it Mass Assignment, Autobinding, or Object Injection)? Does it not become possible that we could guess the role=admin parameter and value and pass that in with the rest of the payload to give ourselves a higher privilege role? Yes! And that's why this is a vulnerability.

Mass Assignment in Flask

Previously, it seems, this issue has only been widely discussed in the context of Ruby on Rails, NodeJS, Java Spring MVC, ASP.NET MVC and PHP. However, when incorporating this topic into Practical Web Application Penetration Testing (PWAPT), I found a realistic way to introduce and exploit the issue in Flask. What you have seen up to this point is Python code and is exactly how this issue manifests itself in a Flask application.

I have not been able to find anywhere else on the Internet that includes Flask in the list of affected frameworks, so consider this a zero-day release of this information. I have not mentioned this to the Flask community, and I don't consider this to be an irresponsible disclosure because there's nothing the framework should do about this. These are valid features of both the framework and the ORM (in this case Flask and SQLAlchemy), and developers need to know when, and when not, to use them. More on that in a bit.

Dynamic Discovery Methodology

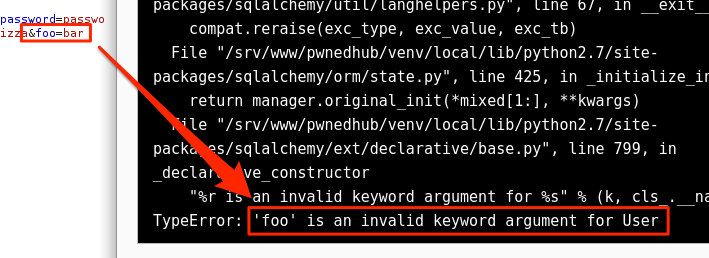

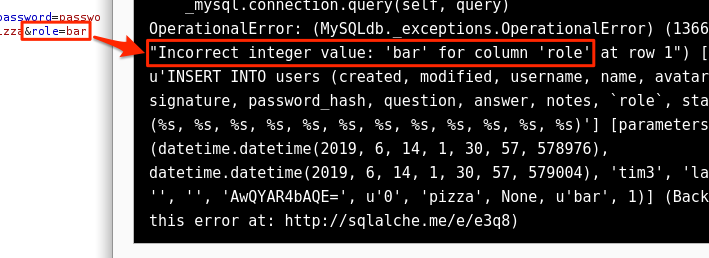

After incorporating Mass Assignment into PWAPT, I approached it as something that wasn't really feasible to find dynamically due to the large number of possibilities (parameter names and value data types) and a lack of meaningful responses. Traditionally, servers just drop unrecognized parameters and don't behave any differently as a result. So I've skipped over it when we were short on time, or glazed over it quickly with the reasoning that it required source code to find. But, remember all the way back up at the top of this article where I said I love to teach because I learn things? I recently had enough time to fully cover this issue with a class and a few of my students, Cal B. (@y0ucancallmecal) and Hitesh Khurana (@tesh_kh), fuzzed the vulnerable resource and noticed some things that I think will be universally applicable in finding Mass Assignment issues dynamically, perhaps even by a Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST) solution (automated scanner).

Ultimately, the simplest form of Mass Assignment stems from mapping request parameters directly to the creation of an internal object by passing the serialized parameters directly to the class declaration, as we saw above. Well, when the serialized parameters are passed to the ORM to create or update an object, the ORM expects specific attribute names and data types according to the model, just like a database table would. What my students uncovered was that by providing arbitrary parameters (attributes the ORM didn’t expect), and values of varying data types for known attributes, they could cause the server to return errors. It just so happens that those errors allowed for the discovery and enumeration of the parameter (attribute) name and value data type needed to exploit the issue, without access to the source code. Based on the students' discovery and my understanding of what the application was saying through the errors it was returning, I came up with the following methodology for dynamic discovery of Mass Assignment.

- Identify possible targets (requests that appear to impact an update or create operation on the server).

- Add arbitrary parameters to the existing parameters (body, query string, JSON, XML, whatever, but the two previous are the most likely candidates).

- If the server responds with an error related to an unknown attribute, argument, parameter, etc., then the parameter name is wrong.

- Fuzz the parameter name until something changes. A successfully guessed parameter name will either work if the data type of the value is correct, or throw a second error related to a mismatched or unexpected data type.

- If the server responds with an error related to a mismatched or unexpected data type, fuzz the parameter value for different data types (integers, strings, etc.). The error may even state what is expected, like the image above.

- When the server stops responding with an error condition, the parameter name and value data type have been enumerated. Go forth and exploit.

Obviously, this assumes some sort of error response to varying input. Finding Mass Assignment without errors (blind) would take me back to my original line of thinking that it is infeasible because there is no way to confirm control over the operation until complete success. I’m still digging into blind discovery, but this is where I stand at the moment.

If you're wondering how applicable this methodology is across other technology stacks, it has been tested on both Flask and Ruby on Rails, and in both instances, the errors returned by the application included messaging eluding to unrecognized attributes for attribute enumeration, and incorrect data type for value data type enumeration. This is very promising and I expect to see similar results most everywhere. Please share your discoveries.

As far as scanners go, I see this being implemented as an injection check. All applications take the same kind of stuff: POST payloads, query strings, JSON or XML. Arbitrary parameters and varying data types are universal. Based on my knowledge of how ORMs work in general, this methodology should cause an exception in any implementation, and when it isn’t caught and handled by the developer, the scanner should be able to detect and report a potential issue using error-based analysis.

I spoke with James Kettle (@albinowax) from the Portswigger R&D team about all of this. He agreed that it seems like a feasible technique, but also said that the Burp DAST does not check for this and made no indication that it would. I assume due to the variable error responses that are possible across server-side technologies. However, James did mention that his Param Miner extension uses some of this behavior to elicit meaningful responses and may help identify the issue. I tested this myself and was unable to get the extension to identify the specific instance of the vulnerability I was testing against. However, the target vulnerability was a registration page that required unique information in specific parameters on every request. Param Miner did not appear to have the configuration options available to do this, but I suspect in other less restricted instances, it will help. As for now, this is yet another reason to have your applications manually analyzed by a trained professional, and not lean solely on a DAST solution.

Remediation

As always, I don't like explaining why something is broken without providing a means to do it safely. There are a few ways to create or update model objects safely.

First, validate input. Applications should always validate input, whether using it as a security control or not. However, in this case, validate provided parameters against a list of expected model attributes. Validation can be done by blacklisting (nonassignable attributes) or whitelisting (assignable attributes), but the validator must be updated any time the affected model changes, and will be unique for every form.

Second, explicitly bind parameters to the model object. Given the example above, it would look something like this:

user = User()

user = user.username=request.form['username']

user = user.password=request.form['password']

db.add(user)

db.commit()

Notice the application is not blindly trusting user input with regards to parameter names (username and password). The application avoids using the binding shortcut and does things explicitly.

Lastly, bind to a Data Transfer Object (DTO) before binding to the final object. DTOs are intermediate objects consisting of an assignable subset of the target object's attributes. It acts as a kind of filter. So first, bind the DTO to the untrusted input, then bind the object to the DTO. This provides similar behavior to that of whitelisting parameter names as it will only use the parameters matching the names of expected attributes.

Please share your thoughts, comments, and suggestions via Twitter.

Tweet Follow @lanmaster53